Key Takeaways

- Much of what we can expect for regulatory developments in 2025 will be shaped by the outcomes of major elections in the EU, UK and USA. In the EU, for example, we expect to see the Commission’s proposal for a revamped Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation, or SFDR 2.0 in the first half of 2025.

- Climate Transition Benchmark criteria are more suitable for transition strategies, whereas the Paris-aligned Benchmark criteria are more suited for portfolios aligning towards the goals of the Paris agreement to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees above pre-industrial levels.

- There is a gap between what is reported by corporates and what needs to be included in aggregated reporting from investors. As a result of this, many regulatory initiatives include scope for using estimates or proxies alongside reported data.

- As sustainability regulations proliferate across the globe, interoperability of different regulatory frameworks is becoming a growing issue. While some global initiatives, like the ISSB standards, offer positive examples, it remains the case that there are important differences in the way different jurisdictions think about sustainability. In many cases, these differences are justified by unique local market characteristics or important political differences.

In late 2023, we looked ahead at ESG regulations in 2024 and predicted a busy year in terms of sustainability-related regulatory developments. And so far, 2024 has not disappointed. In a political environment characterized by polarization over ESG-related policies and election uncertainties, we have still seen:

- The first reporting period for companies subject to the EU’s Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD), reporting under the European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS).

- A broader global rollout of corporate sustainability reporting standards based on the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) standards.

- The finalization of the US SEC climate-related disclosures, and its subsequent legal challenges and developments at state-level (most notably in California).

- Continuing work on SFDR, including ESMA’s long-awaited naming rules limiting the use of ESG terms in fund names unless certain criteria are met.

- The beginning of the UK FCA’s SDR regulation, including the most significant sustainable fund labeling regulation to date.

Much of what we can expect in 2025 will be shaped by the outcomes of major elections in the EU, UK and USA. In the EU, for example, we expect to see the Commission’s proposal for a revamped Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation, or SFDR 2.0 in the first half of 2025. While we do not expect these changes to come into force until 2028 (or 2027 at the earliest), the market is nevertheless eagerly awaiting the Commission’s proposal and if – and how – it may draw on the UK’s experience with a fund labeling regime under SDR.

While we anticipate these changes, we wanted to take time to reflect on some burning questions that we are being asked on a daily basis.

Question One: What benchmark is better: Paris-aligned Benchmark or Climate Transition Benchmark?

As is nearly always the case in economics, the answer to this question is “it depends”. To recap, in 2020 the EU passed legislation outlining minimum standards for the EU Paris-aligned Benchmark (PaB) and Climate Transition Benchmark (CTB). The overall aim of these standards was to enable benchmark providers to develop indexes that supported a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions more aligned with the goals of the Paris agreement.

There are some key differences between the two, but broadly the PaB can be considered as a more ambitious standard.

Both PaB and CTB should demonstrate carbon intensity reduction versus a parent index, with the PaB targeting 50% and the CTB 30%. Both must demonstrate a year-on-year decarbonization of 7%, but this is a more ambitious target for a PaB which will start from a lower base.

Finally, PaB and CTB must demonstrate that they fulfill exclusionary criteria laid out in the regulation. As Table 1 outlines, the requirements for the PaB are stricter than those of CTB.

Table 1. Exclusionary Criteria Laid Out in the Paris-aligned Benchmark and Climate Transition Benchmark

| Exclusions for both PaB and CTB |

|---|

| a) Companies involved in any activities related to controversial weapons. |

| b) Companies involved in the cultivation and production of tobacco. |

| c) Companies found in violation of the United Nations Global Compact (UNGC) principles or the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises. |

| Exclusions for PaB only |

| d) Companies that derive 1% or more of their revenues from exploration, mining, extraction, distribution, or refining of hard coal and lignite. |

| e) Companies that derive 10% or more of their revenues from the exploration, extraction, distribution, or refining of oil fuels. |

| f) Companies that derive 50% or more of their revenues from the exploration, extraction, manufacturing, or distribution of gaseous fuels. |

| g) Companies that derive 50% or more of their revenues from electricity generation with a GHG intensity of more than 100 g CO2 e/kWh. |

A key development for the application of these rules came in May 2024 when ESMA passed its guidelines on the use of ESG terms in fund names. According to these guidelines, ESMA suggests that any fund using general sustainability, environmental or impact related terms, should adhere to the PaB exclusionary criteria (i.e. (a) – (g) in Table 1). While funds using social, governance and transition terms should adhere to the CTB exclusionary criteria (i.e. (a) – (c) in Table 1).

In that way, the CTB criteria – as the name suggests – are more suitable for transition strategies, whereas the PaB criteria are more suited for portfolios aligning towards the goals of the Paris agreement to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees above pre-industrial levels.

Question Two: How can investors use estimated data to meet reporting requirements?

Sustainability reporting by corporates is at differing levels of maturity across the globe. Financial institutions reporting on sustainability matters, however, are typically asked to report metrics that cover their entire loan or investment book. There is therefore a gap between what is reported by corporates and what needs to be included in aggregated reporting from investors. As a result of this, many regulatory initiatives include scope for using estimates or proxies alongside reported data.

Across the EU sustainable finance framework, there are circumstances where estimates are permitted. For example, within the EU Taxonomy, there are provisions allowing for the use of estimates where there is no reported data, but information is available to assess the contribution to a taxonomy objective, adherence to the technical screening criteria, and the minimum social safeguards.

Estimates may be used when reporting voluntarily at entity level under the EU Taxonomy. Similarly, when reporting at the product level, financial institutions can rely on “equivalent information” (company-specific disclosures that closely match the technical criteria and definitions of the regulation). Finally, under the EU Taxonomy and Pillar 3, banks may use estimated data to compute their Banking Book Taxonomy Alignment Ratio (BTAR).

SFDR allows the use of “best efforts” to quantify principal adverse impacts, including by cooperating with third party data providers, external experts or making reasonable assumptions. Even within CSRD – the EU’s flagship corporate reporting regulation – the role of estimates is described as “essential” and reporting entities are able to estimate data, for example, related to their upstream or downstream value chain.

Outside the EU, several regulatory initiatives allow for the use of estimates. For example, the SEC’s proposed climate rule permits registrants to use “reasonable estimates” when disclosing GHG emissions. Similarly, the UK’s Sustainable Disclosure Requirements (SDR) regulation allows in-scope firms to specify the proportion of asset data that has been estimated.

Question Three: What tools or frameworks can help streamline ESG data collection and ensure reporting is both accurate and timely?

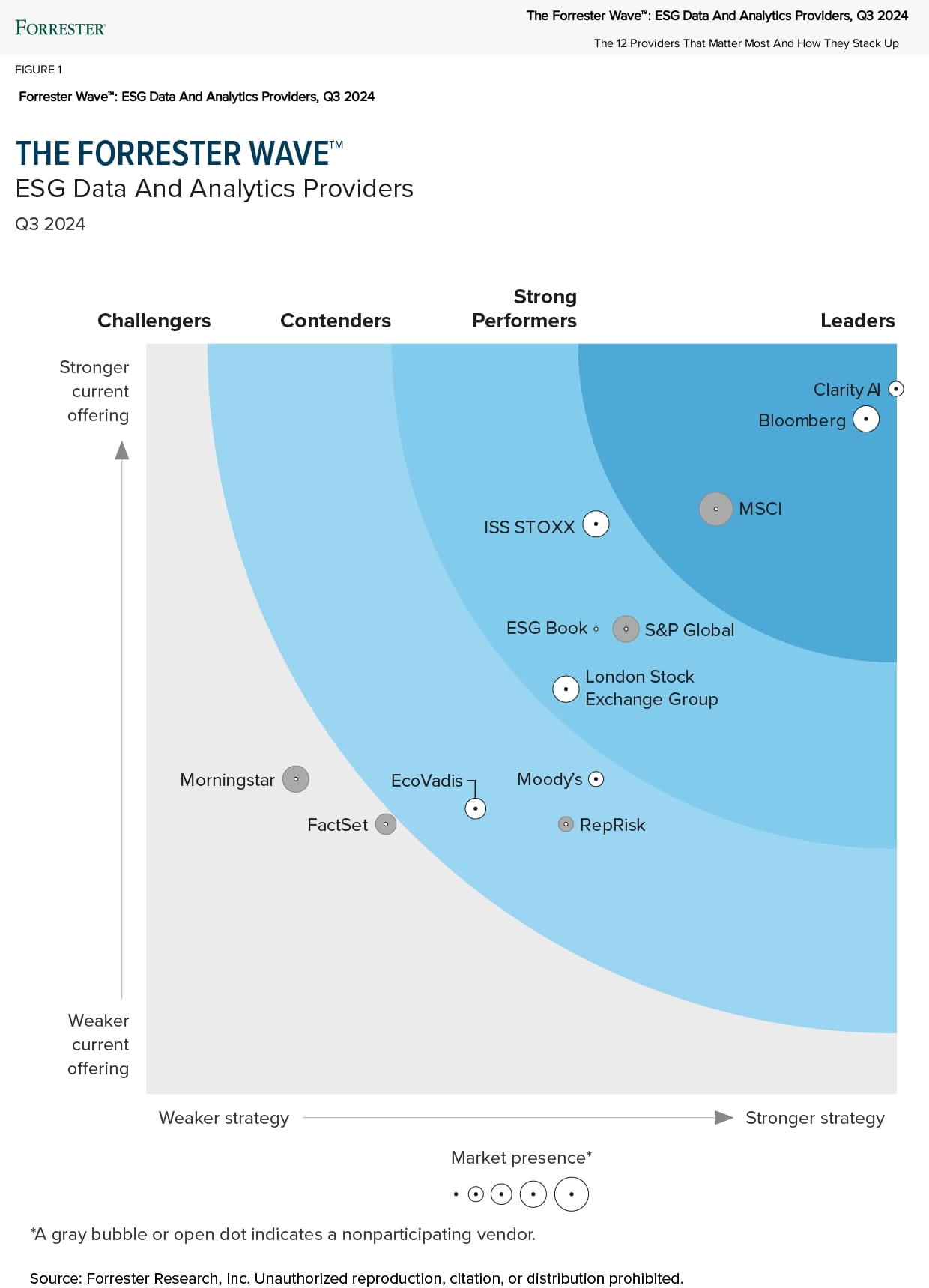

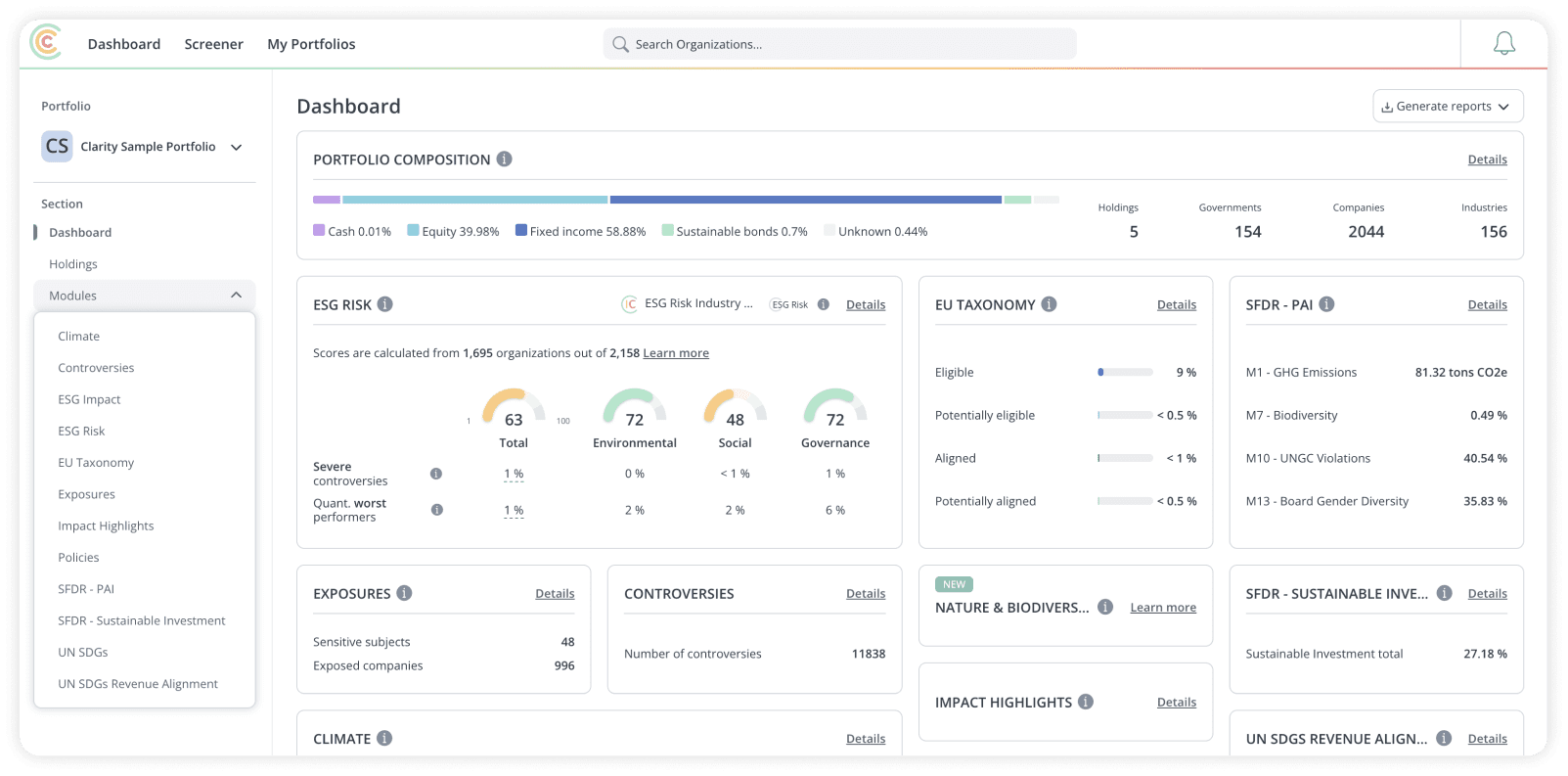

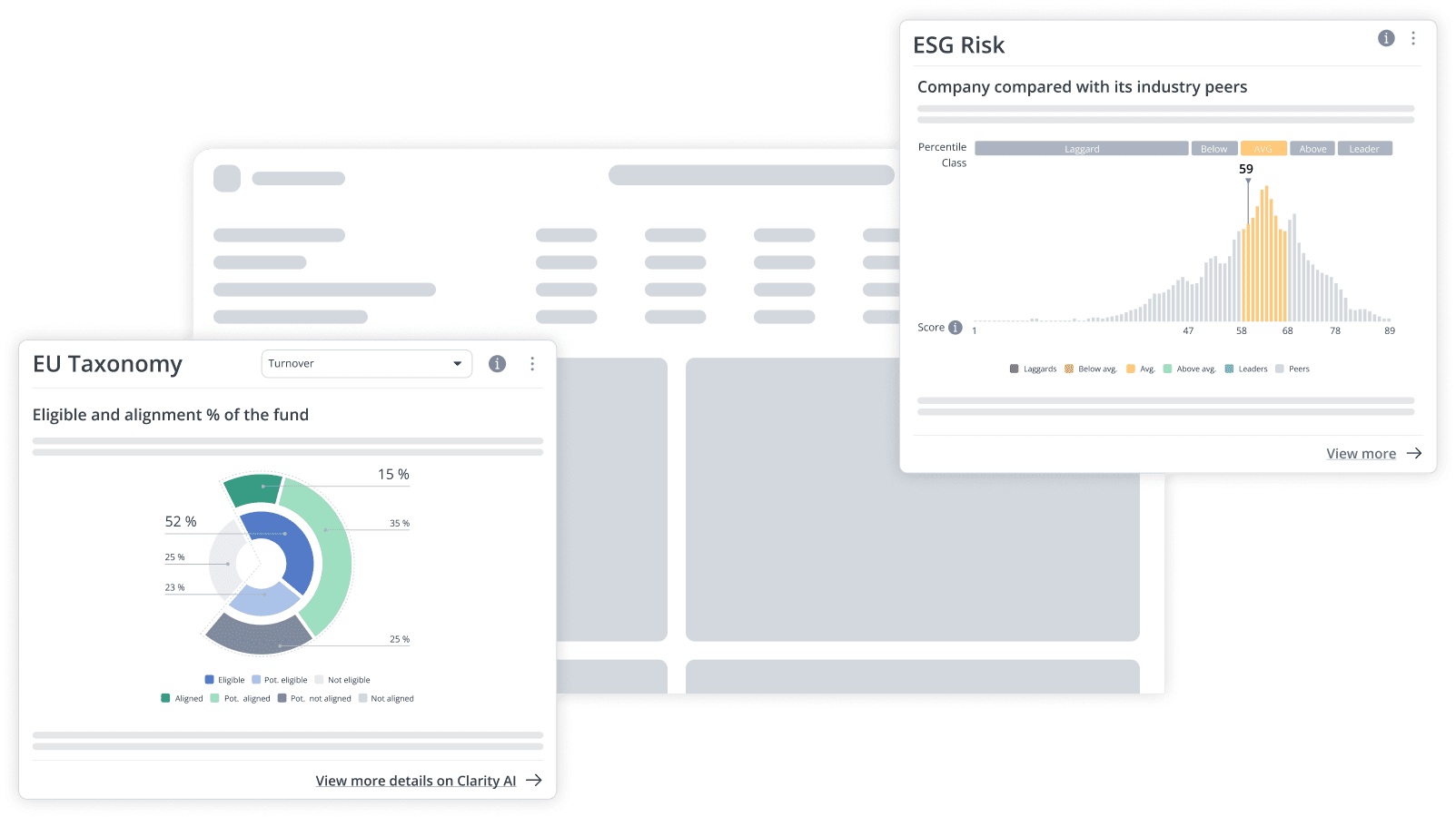

Clarity AI has been a vocal leader in the role that technology can play across a range of sustainability use cases. Tools that use machine learning and AI can pull data from a wide range of sources, such as sustainability reports, news articles, or third-party reports, using natural language processing (NLP). This kind of automation cuts down on manual work and ensures that data collection is consistent, timely, and reliable.

Clarity AI uses this technology to gather relevant data points for a number of regulatory applications, including reporting for the SFDR.

AI also plays a key role in improving data accuracy. Machine learning models can spot outliers and perform reliability checks, giving organizations more confidence in the numbers they’re using. When data gaps exist, AI-driven estimation models, trained and supervised by subject matter experts, can fill in the blanks with a high degree of reliability. This is particularly important for financial institutions reporting on sustainability metrics across entire portfolios, where comprehensive data isn’t always available.

Beyond data collection, Gen AI can also help asset managers in the last step of the process: filling out the official templates. In a recent analysis, we found that automating SFDR periodic reports with generative AI reduced the time required for reporting by over 80%. Not only does this streamline compliance, but it also frees up valuable resources for higher-priority tasks, allowing investors to focus on driving sustainable growth, not just compliance.

Question Four: When will the SFDR RTS level 2 be published?

The SFDR Level 2 RTS refers to the technical standards outlined by the European Supervisory Authorities (ESAs), ESMA, EIOPA and EBA.

The standards underpin the SFDR regulation by offering more practical considerations by, for example, stipulating the templates that must be used for pre-contractual and ongoing disclosures and proposing methodologies for calculating different metrics.

In December 2023, the ESAs proposed a renewed RTS. Among the changes, there was a proposal to include three new mandatory principal adverse impact indicators and a simplification of the SFDR disclosure templates.

At the time of publication, the Commission was given a three-month deadline to review and sign-off on the revised RTS. That deadline was missed and since then there has been an EU election and the implementation of a new Commission. As such, as of today, we are still waiting on those RTS to be ratified, and we are no closer to understanding when they may come into force. In parallel, the new European Commission will propose changes to the Level 1 SFDR in the first year of 2025.

Among other possibilities, the Level 1 review could make more wholesale changes to the way SFDR operates, including revamping the current system of Article 6, 8 and 9 funds. While we await the details of that proposal, it is worth considering that the Level 2 review may be delayed further (or even put on hold) while the Level 1 proposals are finalized. This would reduce the burden on the market of having to adhere to two new proposals at the same time. Finally, it is worth noting that the SFDR Level 1 proposals would unlikely come into force until 2027 or more likely early 2028 at the soonest.

Question Five: How do we integrate ESG data across multiple jurisdictions with varying regulations?

As sustainability regulations proliferate across the globe, interoperability of different regulatory frameworks is becoming a growing issue. While some global initiatives, like the ISSB standards, offer positive examples, it remains the case that there are important differences in the way different jurisdictions think about sustainability. In many cases, these differences are justified by unique local market characteristics or important political differences.

However, this does not make it any easier for international companies trying to comply on a cross-border basis. Take, for example, an asset manager who wishes to market a sustainable fund across the EU, UK, and US.

In the EU, the fund would need to satisfy the SFDR reporting requirements, including ESMA’s naming guidelines. This would require the fund to disclose that 80% of its assets are used towards its sustainable investment objective or to promote environmental or social characteristics. It would also be required to ensure it is not exposed to companies in breach of the PaB or CTB exclusionary criteria.

Moving that fund to the UK would require a different set of disclosures and a potential reframing of the fund’s sustainability objective to ensure it qualified for one of the SDR’s sustainability labels or adhered to the SDR naming and marketing rule. And finally, in the case of the US, it would have to be conscious of the SEC Name Rule which was extended to cover the use of ESG-related terms.

Across those three geographies, not only do the requirements differ in significant ways, but also the understanding of basic terminology like what it means to be “sustainable”, and what we mean by “materiality”, “impact” and “focus”. While we support efforts to converge different regulatory approaches, we do not think these differences will ever disappear altogether.

Therefore, we think it is important that asset managers have a clear understanding of the sustainability objective(s) of their products, the data and KPIs that underpin them, and that they can communicate that in a clear and not misleading way to their end investors. That way, when marketing to investors across different jurisdictions, they can avoid the friction involved in tweaking their fund documentation.