Integrating ESG into investment strategies has become the norm, and technology can help democratize access to ESG information.

As the regulations on sustainable finance continue to develop, asset managers are under increasing pressure to not only comply with regulations but also deliver returns to their clients all without falling foul of greenwashing accusations. And at the heart of it all is the data.

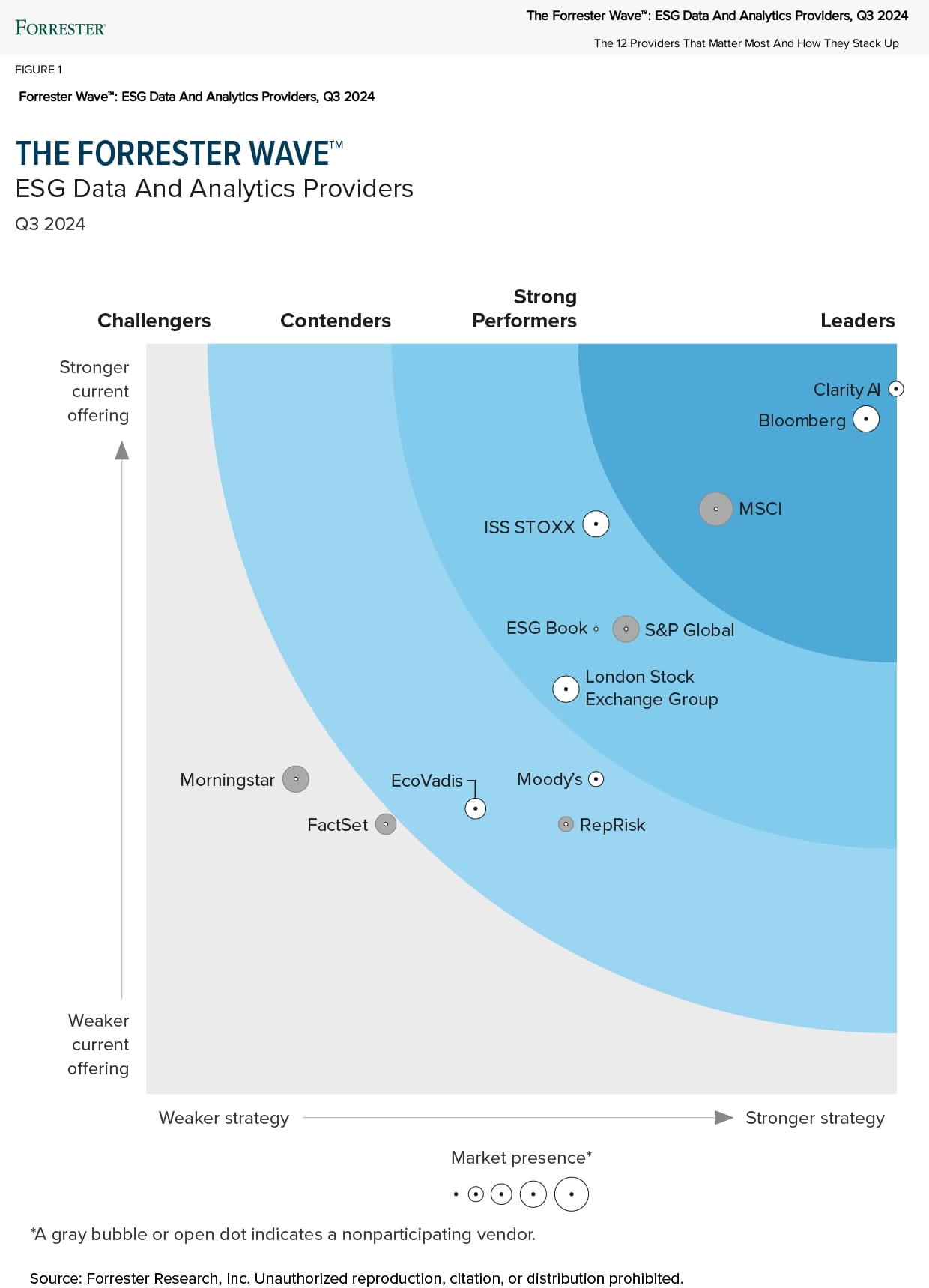

Clarity AI sponsored a webinar hosted by Funds Europe, to discuss the various ESG metrics that are used in the market and the challenges involved as well as to provide some actionable insights as to how these challenges should be met.

Watch the Replay Now

Here is a transcript of the webinar¹, with Borja Cadenato, Director of Product, and Austin Ritzel, Product Specialist, both at Clarity AI; Carl Balslev, ESG Product Manager at SimCorp; and Freddie Woolfe, Investment Analyst at Global Sustainable Equities at Jupiter Asset Management. The conversation was moderated by Nicholas Pratt, Operations & Technology Editor at Funds Europe.

ESG Metrics, Scores and Ratings Decoded

Nicholas Pratt (Funds Europe): Can we clarify exactly what we mean by ESG metrics and what the difference is between ESG scores and ESG ratings, and any other metrics that may be used by investors and asset managers. Borja, could you give us some definitions here?

Borja Cadenato (Clarity AI): Thanks so much, Nik. Absolutely. I will start by saying that ESG metrics are probably the most granular level of information related to sustainability that different companies provide to investors.

These metrics can be as low level as the number of CO2 emissions, any policies a company might have in place on health and safety, or any other governance-related aspect like how many women a company employs or any policy related to that.

So this makes a very different set of metrics that can be used to look at sustainability across companies.

What has happened, I believe, is that given the complexity of all these metrics, several ways of summarizing and aggregating all this information have been proposed in the market.

The most important and frequent ones are ESG scores and ESG ratings. Essentially, these two measures do something very similar. They aggregate all this complexity of different sustainability data into a simple final letter or number that tries to make certain aspects of sustainability comparable across companies.

On one hand, ESG ratings usually are built by analysts and they include personal opinions whereas scores, on the other hand, are more systematic but fundamentally, they provide the same level of visibility.

So this is one framework, ESG. And I think this is another very important point: ESG tries to arrange all sustainability data across the now very popular and well-known pillars of environmental, social, and governance topics.

But this is just one framework, one very popular framework, but there are other frameworks as well that try to look at sustainability from other points of view.

So ESG -this is very important as well- tries to look into how sustainability might impact a company and answer this question by looking at how those sustainability metrics are relevant for those companies.

On the other hand, there are other frameworks such as impact frameworks, like SDGs, or regulatory lenses like the SFDR regulation in Europe that also try to tackle these aspects.

Nicholas Pratt: Great. Thanks very much for that. I’m sure that will be a useful guide as we go on through the webinar to address some of those issues. And as I mentioned at the beginning, we like to be interactive. So we’re gonna be interactive early.

We have a poll question for the audience. The question is:

What is the biggest challenge when it comes to incorporating ESG metrics into sustainable investment for funding?

A- Limited transparency in ESG reporting making it difficult to assess the accuracy and reliability of data

B- Limited view on sustainability with some factors and themes not being adequately considered

C- Difficulty in accurately measuring the impact of ESG factors on investment performance?

So, in essence, A- Accuracy, B- Availability, or C- Application.

The Value of ESG Ratings

Carl Balslev (SimCorp): While we’re waiting for the results to come in, I’d like to add something to the definitions given by Borja. I just read a survey recently called “Rate the Raters,” in which they suggested that 94% of all investors actually use ESG ratings. So the top level, the most subjective ones, even though maybe they put limited trust in it. They’re actually used, at least once a month, by 94% of all the investors.

Nicholas Pratt: So, ratings are possibly used more than scores you would say.

Carl Balslev: There’s a lot of discussion on what is the value of ratings, but it’s still very much used. Maybe it’s just for screening or just to give a high-level indication and then you can dig into the details later. But they’re still very much in use.

Nicholas Pratt: We might discuss that point in length as we go on. Ok, just to summarize the results. What we have is the application of ESG factors on investment performance as the main one, with sort of 44% of respondents. That’s useful given that that is essentially the title of this webinar. Hopefully, that 44% of people will be a bit more informed in 44 minutes or so. But no pressure, panelists. We’ll go to the first question, which is what exactly are the problems with ESG scores. So Carl perhaps you could start us off here.

Limitations in ESG Scores

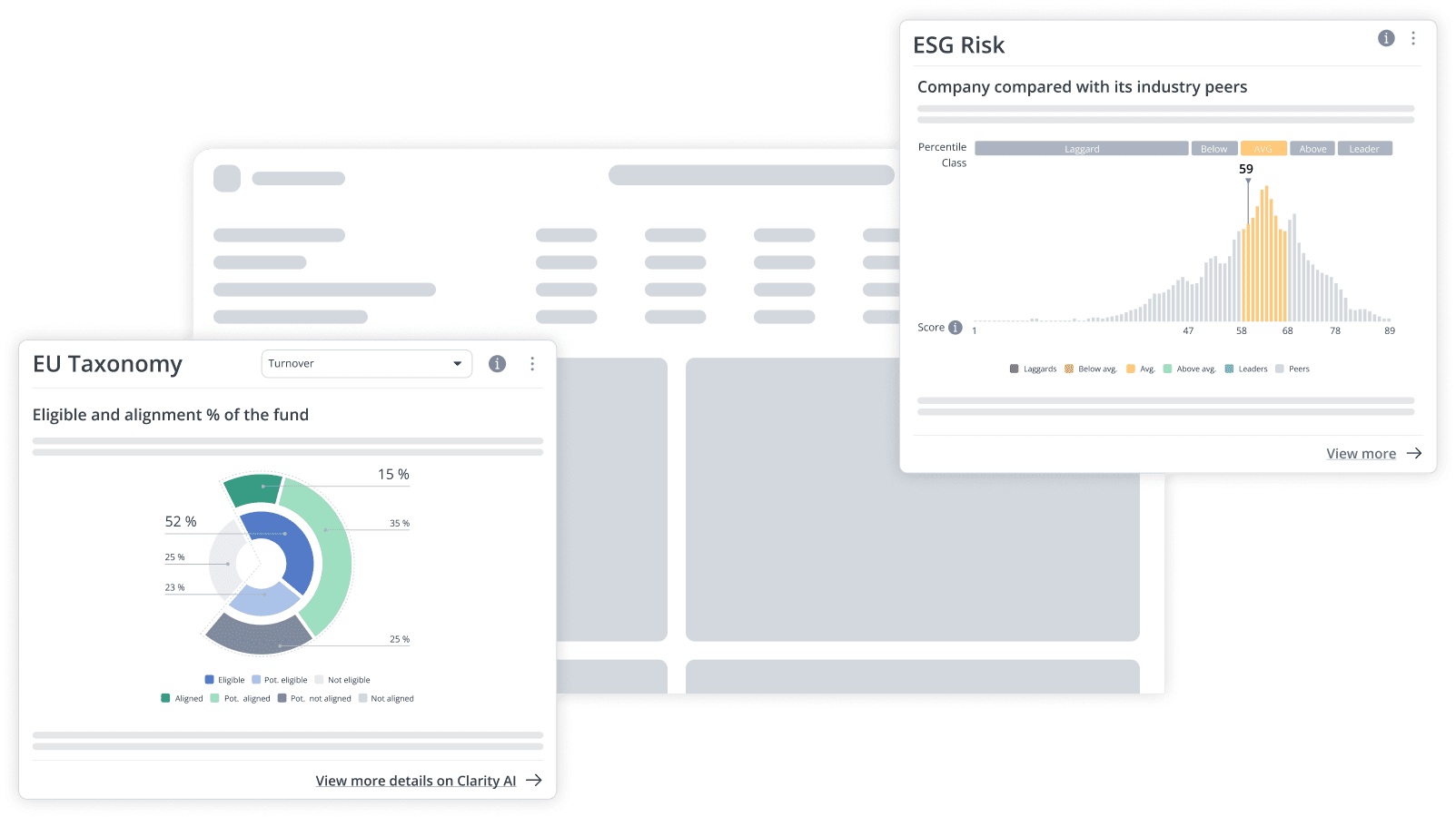

Carl Balslev: Just from the helicopter view, the top level: when you try to condense a number of different topics into a single measure or just maybe a handful of measures, then that has limitations and then also it can cause a lot of problems.

There’s a risk that you expose yourself to some problems. And I think the biggest problem is with your own clients. So if you’re an asset manager and investment manager, then your clients will have their own view of sustainability and that may not be totally aligned with the numbers that you use in your strategy. So I think on the highest level, you want to be very clear in your communication about what it is that you do in terms of ESG and also why you do it. So what is the goal of your ESG program as an investment manager?

Nicholas Pratt: I guess in essence, what you are saying is that it’s not the score itself, but that the problem is how you use it and communicate with other counterparties. How you use it so that I guess you both have the same understanding.

Carl Balslev: I think the key is communication and alignment with the understanding of your clients.

Austin Ritzel: I think Carl’s right on the money when it comes down to the difficulties that you encounter when you try to condense a diverse array of factors, into a single score. I think fundamentally one of the challenges that we encounter is really this pernicious and very false-headed belief that the way to approach ESG is monolithic, right? And that the investment industry’s approach to it ESG is monolithic. We know in fact that that is of course not true, right?

So for an asset manager that’s early on in their ESG journey or for whom perhaps ESG is not, at this point, a driving strategy at their firm, that condensed score, that high-level score may be very effective, right? That may be all that they need.

However, for your more sophisticated asset manager that’s been doing this for 20- 30 years, back before it was called ESG and you know you’re working with SRI, for them, they might want to go into a very deep level of granularity and understand precisely what are the levers being pulled to influence that score.

And then beyond that, I think another issue is that, for those especially sophisticated asset managers, their years of expertise, you know, that have really sharpened their sense of ESG and their beliefs may not be reflected in something like a default SASB informed materiality map.

And there are two sides to this. Number one: provide the granularity necessary to satisfy the more experienced investors while also retaining high-level views that are helpful for your less experienced ESG investors.

And then on the other side, also provide those levers of customization to satisfy some of those needs to inform an ESG strategy with one’s own years of views and preferences, and perspectives on ESG.

Nicholas Pratt: I guess you’re saying it’s not necessarily that you need a two-tier approach to this for retail investors and institutional investors. It is possible to cater to both sides of the market with generally this same overall frame.

Austin Ritzel: Yes, I think fundamentally that that is possible. Borja and I interact with clients every day at Clarity AI and those are two constituencies that we have to actively serve. And you know, we have to present the same sort of framework to them, but the levers around that framework can be very powerful.

And I think that’s where that level of customization and the ability to go down to an extremely granular level to satisfy both sides of the equation is really helpful.

Nicholas Pratt: I see. And Carl, when we’ve talked about this previously, you talked about the importance of a materiality framework and that perhaps that’s difficult for retail investors to understand. So it’s that something that can be easily addressed?

Carl Balslev: I think it goes back to what Austin was saying that institutional investors would have been working with this for many years and have the language of materiality maps, for example.

Also all of the frameworks, all of the standards that are known, that’s something that institutional investors really understand and they can ask the right questions, they can challenge the asset manager, which is providing the investments on behalf of you.

But retail clients, they don’t have the same vocabulary. I mean, even though the underlying strategy may be the same there are these different levels of sophistication in terms of the language and understanding of the framework. So the underlying strategies would be the same, but there has to be some kind of more simple and maybe more straightforward communication to most of the retail clients.

And then perhaps also the ability to drill into the more advanced, the underlying data, the evidence in the data also for retail clients, in case there’s somebody who wants to look into that, so to create that trust in the methodologies.

Nicholas Pratt: Freddie, as the fund manager on the panel: are there any sort of obvious problems that you see with ESG scores and how maybe you use them or how you communicate them to your investors?

Freddie Woolfe (Jupiter Asset Management): I think a lot of it’s been covered. This point is so important, you know, it is just an opinion. And actually, that’s kind of right at the center of doing this. Right, this is about being informed to make a decision rather than just sort of blank it, relying on a score or some other data point that essentially absolves you of the responsibility of having to do that work and make that decision.

So all of this point about data providers not agreeing with each other, you know, the raters not agreeing… It’s actually not negative, it’s positive because it’s a core part of doing it well. I can make two other points on this.

One is that one of the big areas where they tend to agree if you look in the academic literature is around outcomes. So policies. Does a company have a diversity policy, does a company have a policy to reduce its carbon emissions? Those sorts of things are easy to assess and generally not all that kind of subjective.

But if we’re talking about sustainable investment, then the core consideration is kind of what’s happening on the ground here. A slight concern is that ESG scores encourage the disclosure game, which some corporates are very good at playing, rather than necessarily: what does this mean for performance and outcomes for people and planet, and for clients.

So you know, how companies are contributing to a more sustainable world is the question and that’s sort of much more complex and much more activity and evidence-driven. That is one area that you need to really get, many layers beneath when thinking about ESG scores and how they can help in a sustainable investment process.

The other area which I think is really key to be thinking about is ESG scores and data. In general, they are by their nature backward-looking whereas investment is very much about what’s going to happen in the future, in sustainability. As an example, it’s quite possible that a very carbon-intensive business today could if you believe genuinely that it can do this in a credible and committed way, could absolutely become a leader in the low-carbon transition. And that could make a really interesting sustainable investment.

Obviously, the question is: is it going to be able to deliver that credibly? And then is it also going to do it in a way that’s going to make it a good investment? But the point is you need to be kind of taking a forward look at what companies are going to be doing and that tends not to be particularly well served by ESG data, which is sort of backward-looking.

So you need to get beyond the policies and disclosures and into kind of what these companies are actually doing. And then that framework will help you take a view as to whether they’re going to be a good investment from a capital allocation point of view through a sustainable investment lens.

Nicholas Pratt: And so, on that point: is that ultimately direct engagement with these companies or is there a way, I guess to get beyond the headline scores whilst still sort of dealing with the data?

Freddie Woolfe: Obviously, engagement with Corporates is a big piece of it. You know, our sort of bread and butter day-to-day is building conviction in a world of uncertainty, right?

That’s what we do in investment and you sort of have to be comfortable in that kind of environment. So it’s not a particularly different framework to much of the work that we do in other areas of investment. And one of my bugbears is that for some reason ESG sustainable analysis tends to get treated rather differently.

We tend to treat it with less rigor, we tend to sort of believe that we can address it much more readily, much more easily and then it gets put aside, it’s a tick in the box whereas to do this properly, a lot of the investment skills can be applied.

And a big part of that is dealing with some of this uncertainty understanding the nuances, understanding how you think about competitive dynamics, and how industries will develop over time.

What do opportunities look like, what do returns look like, and can companies deliver on this stuff? So, you know, it’s really deeply embedded into what we do day to day already. But thinking about a broader set of stakeholders and a wider set of value creation.

Reporting on ESG

Nicholas Pratt: On that point in terms of sort of treating ESG differently to maybe other metrics. Borja, do you see any sort of parallels between how the reporting of financial risk and say IFRS standards? Should we be taking the same approach as we would with that kind of data as we would with ESG data?

Borja Cadenato: Absolutely. I think that connecting to the previous points, something very important about ESG scores or ESG ratings is that they, as I said at the beginning, try to simplify a complex reality and it’s fundamental to understand if needed, what is behind that reality. And that involves knowing what you are measuring, and what metrics you are looking at. And what are you doing when that metric is missing for a given corporate. You need to make sure that if two Corporates are giving disclosure on a metric, they are comparable, for instance, and then you need to understand how that ESG score or rating is aggregating all that, rolling it up to the final number.

I see, going back to your question, that there is a parallel in how some level of homogeneity and comparability is very much needed when we look at those low-level metrics because otherwise there is the chance that different Corporates will be reporting on the same issues in different ways that are not comparable and that will only contribute to more confusion.

So I see this way forward where there is this consensus and more standards into how companies report on some fundamental issues to make sure that there is enough coverage and everybody can have access to that basic information and that data is consistently provided.

Then I also agree that when we aggregate all that different sustainability data all the way up, it’s important that different ESG companies do that in different ways because I think there is some value in providing different values there. But I think that at the very basic level, those sustainability metrics provided by Corporates that need to follow a consensus.

And I believe in a certain way, that’s what happens with other financial data where all the companies try to report in pretty much similar ways, and then different analysts try to make their own views.

Nicholas Pratt: I see. So it’s I guess using the same basic rules to report the numbers. But, obviously a variation in what those numbers are. In terms of developing standards for this, how would you say we’re progressing? And I guess what are the potential downfalls to getting more sort of consistency in standards?

Austin Ritzel: That’s a difficult question. I think we encounter a number of challenges that Borja’s already illuminated.

I think in some ways if we look, for example, at one of the frameworks that’s really having a moment and that has had a moment for a few years now: the SDGs, as a particularly salient framework for retail investors, we find a good example of some difficulties wrapped up therein.

So if we think about the SDGs as a framework, and the upsides before the downsides. It’s a pretty universal, as universal as you can get, adopted by 193 un member states recognized by somewhere between 50% and 80% of, for example, the US population. And you know, the friendly iconography, I won’t deny has also played a role. But more fundamentally, they touch on issues that are very easy for individuals to understand; things like no poverty, no hunger… It feels like I’m gonna break into a John Lennon song in just a moment. It’s fundamentally a salient global business plan.

However, in thinking about how we map and demonstrate contribution against the SDGs as a sort of nascent investment framework if you will. We’re looking at 17 goals, 169 targets, and 232 indicators that were designed for governments, not corporations.

So that’s your first fundamental stumbling block in, you know, arriving at a framework that is both salient for investors and readily understandable but also actionable. Narrowing down those goals and targets to their actionable constituents is your first challenge.

But on top of that, you really run into a thicket when you start talking about assessing something like contribution, right? Do you quantify and monetize company impact or do you align revenues to the SDGs, and you know, parenthetically we do both, but we recognize that there is very little consensus on either, right?

So again, you come back to the challenges around these frameworks, a lot of it is we just can’t agree on how we like to do it best. And that’s, to Freddie’s point, not necessarily a negative thing. A part of me thinks that we are sort of in this Cambrian explosion to put it in evolutionary terms, of sustainability. And we’re trying out a lot of different things. Most of it will probably fail, right? As it did statistically with evolution. But the things that succeed, the things that went out will be true winners.

So, you know, we do encounter a lot of challenges, a lot of friction, but I think that friction is actually a very powerful lubricant for improvement. Not to be too saccharine, but that does give me great optimism when we talk about the potential of these frameworks.

The Case for Considering ESG Metrics, Scores, and Ratings in Your Investment Strategy

Nicholas Pratt: Great. I want to sort of focus on some more specific questions, and I guess one of them is, I mean, obviously everyone on the panel is fully invested in sustainable finance, be that financially or philosophically. But that’s not necessarily the case for every participant. So, do you think ESG metrics are a necessity even for firms not interested in creating sustainable products? Borja you want to go first on this?

Borja Cadenato: Yes. And I think this comes back to a fundamental question which is whether you want, as an asset manager, to build a sustainable product that focuses on outcomes, just as an example and to Freddie’s point before.

Even if you don’t want that, I think that sustainability, be it metrics or scores, is just another fundamental ingredient in the assessment and analysis of Corporates. So I think that even if the focus is not to build a sustainable product, all those aspects are fundamental today to understand how credible companies’ strategies are and they need to be assessed, not as a separate type of data, but just as another fundamental ingredient into that evaluation of companies.

So yes, definitely, I think that all this data is really necessary for the assessment of your investment process, even if the outcome is not a sustainable product.

And, I really think that one of the benefits of the focus we now have on ESG is that disclosure has improved, data is more comparable and it’s become much easier for all these investment firms to capture all this information and include it into their investment processes.

Nicholas Pratt: Great. Thanks, Borja.

Austin Ritzel: Nik, I can hop in very quickly. I think Borja covered a lot of fundamentals there. One I would add is that if you aren’t interested in creating sustainable products, I think that Borja covered the need, you know, to invest in ESG elsewhere, right? Is just a risk management strategy, capital protection.

But I think more fundamentally, you really do have to reassess that strategy in light of what we see in the market today if you aren’t offering any form, of what we would call sustainable products, right? We’re seeing that with the convergence of some hugely substantial trends, we’re heading toward the largest intergenerational wealth transfer in history between $30 to 70 trillion is going to be transferred from the hands of baby boomers to the bank accounts of millennials. And wouldn’t you know it, according to Morgan Stanley’s latest sustainable survey, 99% of millennials are interested in sustainable investing. So this is a world in which sustainable investing is no longer an exception, but rather an expectation. And I think if you are a fund manager that is a world worth preparing for, right? Just from a self-preservation point of view.

Nicholas Pratt: I see, yes. Thanks, Austin. I guess another concern with sustainable investing becoming so sort of data-driven is that there are so many reporting requirements that only the firms with the resources will be able to compete. So Carl are we already seeing larger firms getting ahead in this or is this already a problem?

Carl Balslev: I have to admit that in my company, we mostly deal with very large investors. So we’re covering the really high end of the spectrum. But definitely, there’s an advantage of the scale here so they can invest in ESG teams and build up their capabilities.

I think there’s a benefit there in following the standards and creating something that can be brought out at scale to many clients, even the most sophisticated approaches.

The Role of Technology in Increasing Availability of ESG Data and Democratizing Sustainable Investing

Nicholas Pratt: Is this an area where technology can help make it a sort of more democratic process and lower some of those barriers? Or is this still such an evolving area that it may take some time for that kind of technology to have an impact?

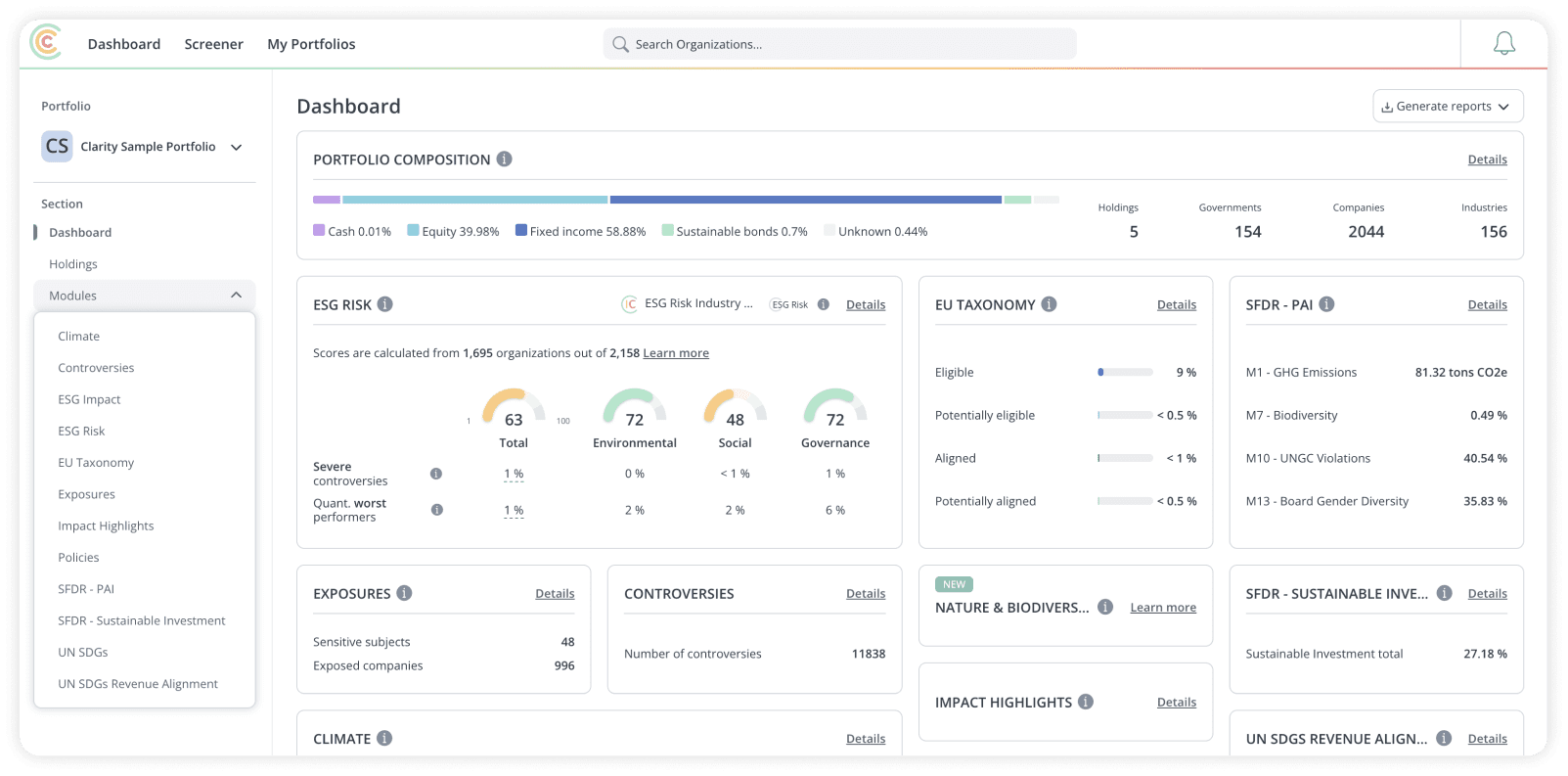

Borja Cadenato: You are absolutely right. Technology has been instrumental in fast democratizing access to this information and help in collecting this information on a larger scale from companies.

So, for example, in Clarity AI, as you mentioned, we are using today Artificial intelligence and machine learning in estimation models to fill many gaps that exist today in data reported by companies. We are also using Natural Language Processing to analyze millions of data points every week on a scale that only technology can provide.

And for certain specific metrics, this helps to level the field on the degree of information that you can obtain from different Corporates. I believe that as time goes by and companies will probably continue improving the disclosure of this information, this will only improve. So I’m quite convinced that we are moving in that direction.

Carl Balslev: I definitely think that also regulation will help with disclosure. So more data will be available. Of course, companies like Clarity AI are helping spread the information, but definitely regulation is a big differentiator here.

So when it becomes mandatory for companies to disclose all this data then that data will become available. However, it’s backward-looking information, as we discussed earlier.

Nicholas Pratt: Thanks Carl. So we’re getting lots of audience questions in, which is great. And so I encourage panelists to have a look at those and we’ll come to those shortly.

Before we do, I wanted to touch on the specter of greenwashing and how you make sustainability claims at minimum risk using ESG scores or ratings. And how do you avoid greenwashing accusations? And, Freddie, we’ve not come to you for a while. So I’m sure you’ll be delighted to go first on the question about greenwashing.

How to Leverage ESG Metrics and Scores to Minimize the Risk of Greenwashing

Freddie Woolfe: Sure. I think it’s a really important topic. If we’re going to be delivering better outcomes for clients that are aligned with better outcomes for people and planets, the authenticity behind the claims that we’re making is sort of absolutely fundamental. I guess I’d make a couple of points on this.

So I think probably one of the most important aspects here is that you as an investor own the assessment of what we’ve talked about, some of the challenges with the ESG scores, and the ways to get through that. And part of that is that you do need to open yourself up, to understand exactly what you’re investing in. And to do so, you need to get into the weeds. So, you definitely open yourself to challenge if you’re making claims of sustainability, but haven’t done that work to assess how those assessments have been made. That would be sort of my number one recommendation.

It is absolutely fine to have a difference of opinion. I think as long as you can show how you reach that conclusion and obviously, the process and approach are reasonable. There will always be people who will disagree with you.

And after all, and again, going back to sort of bread and butter of investing, this agreement is what makes the market right? But you do need to be able to explain how you reach that opinion.

And I think for it to be credible, it has to be much more than a kind of well, someone else’s score told me that it was OK so I did it or, you know, someone else didn’t tell me that this business was doing that or I hadn’t quite realized it. So I think owning the assessment is a really important part of it.

The next, and you know, it’s interesting this discussion about firm-wide strategy and positioning yourself as sustainable products, and where ESG belongs. And should you have a sustainable investment strategy in your business. Within all this greenwashing dialogue, I think a really important part of it is you do need to be really careful about the extent to which you claim that sustainability is integrated into investment processes.

So we’re seeing a lot of flows, a lot of some really impressive numbers that we discussed on the extent of the wealth transfer and the proportion of next-generation investors that want to see their savings invested sustainably.

The flip side to that is that it is quite evident that the kind of clients, consultants, and regulators are getting much better at seeing through a lot of the marketing and being a lot more incisive about how important this is to an investment process.

So being really careful and genuine and authentic about the relevance and depth of the analysis, you know, things like a client asking to discuss your approach, sustainable investment, but then sending a central ESG team that doesn’t make investment decisions in it isn’t likely to pass muster.

And I think, to make this more of a positive statement, the key is actually to tell it how it is. And if in that process, the strategy for you, it becomes clear that you could do better and clients would like you to do it differently, then that really gets back to the kind of philosophical aspects, we’re talking about. Kind of why you do it. And then I think going through that process and addressing it then becomes a win-win for everyone, but you have to go into it with that authentic view. Otherwise, absolutely rightly, you do open yourselves up to criticism.

Nicholas Pratt: Sure. So I guess would be authentic and with that, do the work and show the work. And Carl, I think you’ve talked about this before. The need for checks and balances in that process. So is that an important part of this as well?

Carl Balslev: Yeah, I think that there’s also the type of greenwashing that is unintentional.

So you can have all the good intentions, but if it’s not implemented in your operational processes correctly, then there might be some investments that are slipping through the compliance checks that you have, or maybe in some other kinds of controls, whatever you have in place. This is also the focus area of my own company SimCorp, as we are selling a platform for investment processes.

But we see a lot of our clients when they onboard ESG programs in the operation processes, the focus is actually on the compliance part. So of course, they need reporting disclosures to regulators, and the PMs need the overviews, the high-level management and the ESG teams need to know where is the enterprise going across all of my portfolios. But definitely compliance is important, that’s why you really encode the ESG program policy really consistently. So that’s really a key thing, and it’s a system implementation of how to avoid greenwashing.

There’s another part that is more related to how much you own the ESG program as the team was saying. So it’s not enough just to provide the information; it really has to be something that you have a clear policy for. You also need to have some clear objectives as a PM.

When you take an investment decision, there are all kinds of analyses going on and that has to be implemented not just in the system but also as a sort of change management program for your whole organization. So it has to be associated with the right incentives for the PMs for them to take their decisions.

Nicholas Pratt: I see. Thanks.

To watch the full webinar and the Q&A that followed the panel discussion, please click here.